BY NUR SYADA

ARTWORK BY SPUKITOWN

When you’re a socially inept 16-year-old girl stuck in the small town of Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, what else is there to do?

My usual routine in a town where every store closes at 7:00 PM sharp is being cooped up in my room, finishing the final episode of American Horror Story: 1984 instead of studying for SPM. As I think about all the studying I should be doing while the horror anthology series plays on the screen, I hear a certain sound that brings me back to reality — or maybe someplace better that I have yet to leave.

I remember a scene where the camera panned to a dead body accompanied by a haunting opening riff I had never heard before. I immediately focused on the lyrics and thought, “I need to hear more of this”. Even at the time when I had no idea what song that was and who was behind it, I felt a certain shiver in my bones as to how fitting the song is with the scene, having an ex-serial killer realising he can never escape his past, along with a mysterious voice singing “I am the son and the heir” in the background. After the harrowing scene, I wasted no time and looked up bits of the lyrics I managed to make out.

It leads me to “How Soon Is Now” by The Smiths. And then I felt something growing in me: a terribly romantic love affair with a band that broke up almost 40 years ago. I sit on my bed and ponder: I know I have a lot to catch up on.

Those first few months were the ‘honeymoon phase’, not that I know what it feels like to live through one. Morrissey himself once said that the closest he got to romance was when someone stepped on his foot in Woolworth’s in 1982 — so don’t expect much from a girl like me. But unlike unfortunate romantic relationships, this honeymoon phase with The Smiths feels like it lasts forever. It’s a long, slow journey of blissful indulgence, a shocking revelation, an epiphany for a teenager to realise that Morrissey is singing all the things I’ve always wanted to hear.

And like stepping into a never-ending pool where the deeper you go, the easier it is to breathe, I made my way into their discography. Starting with their self-titled debut, which remains my favourite until today, and ending with Strangeways Here We Come, a final masterpiece from a fully developed band. “Hand in Glove” pounded my head with its drums along with the passionately painful lines “If they dare touch a hair on your head / I’ll fight to the last breath,” and I Won’t Share You marks the end of all four studio albums with its own tragic way of bidding goodbye: “I’ll see you somewhere / I’ll see you sometime, darling.”

I became enthralled by The Smiths’ aesthetics — flowers, 60s film stars, the wits of Oscar Wilde and every single thing that made them unique. And like most things, I wanted more, so I plunged deeper into the pool.

It’s easy to let myself get taken away by Morrissey’s solo projects in the early 90s and early 2000s, such as Kill Uncle, Vauxhall and I, You Are The Quarry, and Years Of Refusal. Several years later, Vauxhall and I remains close to my heart, an album that gets better as I grow older. With songs like “Now My Heart Is Full” and “Lifeguard Sleeping, Girl Drowning” making their way straight to my “comfort song” playlist on Spotify, I think Vauxhall and I is one of those albums that would not work if made by anyone else. As much as The Killers’ Brandon Flowers thought he did a good job covering “Why Don’t You Find Out for Yourself,” it doesn’t radiate the same warmth as the songwriter himself. It became a friend to me, a then-16-year-old outcast, and the album made me feel like perhaps whatever happened is not the end of the world, which is why I keep coming back to it every day. My attachment to Vauxhall and I just grew stronger. Sometimes I do wish I could just drag the vinyl wherever I go. “Speedway” concludes the album with the haunting line “In my own sick way / I’ll always stay true to you,” a line I repeat to myself like a mantra sometimes. Maybe you have to be a little strange and sick to stay true to a certain thing even after all this time. But maybe I am strange and sick.

It feels like fate. Morrissey, arguably one of the godfathers of sad indie rock, has blessed me with scriptures made out of poetic wit and his quiffed-up hair. I was just a teenager who had no idea who she was and what would become of her. Watching the finale of AHS: 1984 transported me back to that year. I immediately got myself a pair of those black-rimmed glasses. I looked stupid, so I stuck with my glasses instead, but other than that, everything else changed. I was a new man or woman; I learned that it doesn’t matter what I am anymore, at least I know who I am and what I can do.

Perhaps that was the first time I finally realised that life will not end just because I look, talk, think and act like this. I realised that I could just turn away from those who laugh at me, from those who tell me I’m too much and never exactly how they want me to be. I can consume all the antipsychotics I want, but a hole in the heart is still a hole, and the first listen of “How Soon Is Now” that night brought me to a never-ending discovery of many different corners that I never knew existed, filling that hole with love. I was too much, yes, but I learned that it was okay to be too much, that someone was singing about this exact thing I was feeling 40 years ago, as cliché as it sounds.

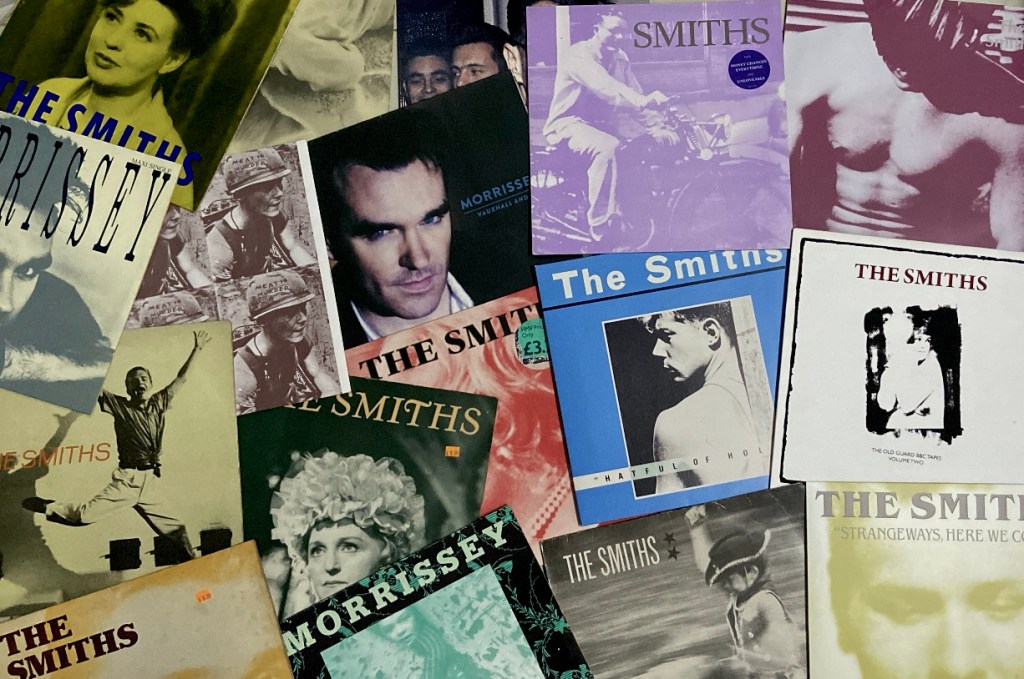

After high school, I got a job as a waitress, and with my first salary, I bought myself a crappy record player along with two second-hand records I managed to find for cheap on Carousell: Hatful of Hollow and, from the solo vaults, Your Arsenal. I dived into record collecting to get the proper ‘80s feel, and I’m glad that’s what I decided to spend my first-ever salary on. With both The Smiths and solo Morrissey having loads of 12” and 7” single vinyls with different covers, fonts, and etchings on the discs, there’s always something new to look at and appreciate.

The minute I got my physical copy of Hatful of Hollow, holding its gatefold cover along with a picture of the boys inside, I never wanted to put it down. It’s a beautiful experience, hearing your favorite songs while having something to look at and hold in your hands. Since then, I’ve scoured every inch of different record stores around Klang Valley and slowly bought all The Smiths and Morrissey records they had with the little money I earned from my job, from studio albums to rare 7” singles. Nowadays, if you walk into Amcorp Mall looking for a The Smiths record, you probably won’t find any left. Trust me, I always get there first.

Fast forward almost five years later, I’m still a socially inept yet somehow fully functioning 21-year-old human being whose room is cluttered with The Smiths vinyl you don’t even know exists, a copy of Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey, James Dean posters, a New York Dolls t-shirt, and an abundance of poems I wrote that remain hidden from the world. I think every dedicated Smiths fan will, sooner or later, follow in the footsteps of either Morrissey or Marr. By that description I made of myself and the absence of a guitar in my room, it’s obvious I chose the former.

The sadness of that 16-year-old girl stuck in her room never left, and in this day and age true happiness seems like a joke, and that joke isn’t funny anymore. But in The Smiths’ book of guidelines, to be sad and hopeless doesn’t always mean to end it all. Why do you think those lyrics were paired with Marr’s riffs, Rourke’s bass and Joyce’s drums? To be unhappy is also to get up and force yourself to still dance along with it, yes, force yourself.

As I am no longer an isolated high schooler and now must face the harshness of Kuala Lumpur in this adult life, I wake up every morning moping about what the day brings, as one naturally does when you live in this cruel city. Stepping onto the packed train every day with hands that somehow never stop shaking, I put my headphones on and zone out to “Rubber Ring” and “Still Ill” sighing at this life I’m subjected to while still living it. That is what The Smiths do to you, I think. By day I listen to “I Don’t Owe You Anything” “Nowhere Fast” and “Shakespeare’s Sister” to get me through and tolerate my bitterness; by night I lull myself to sleep with “The Hand That Rocks The Cradle” and “Well I Wonder.” Even though I know very well the next morning I’ll wake up as miserable as I did today, and perhaps during the weekend I will scream and cry and curse the air, at least in those moments when I have my headphones on or my records are spinning, the rest of the world seems to disappear.

When you are fated to be different and grow up being told to fix yourself, life becomes a never-ending cycle of desperately finding an identity now that you’re older and also trying to stay alive while doing so. But at least now I have a hand that holds me along the way, or more accurately, a voice. I read, I write, I pursue my passions, and I’m not scared of speaking my mind anymore. Perhaps that is the importance of The Smiths, the importance of Morrissey — making the frightened ones see that it’s okay if people disagree with you. Just say what you believe, and it’s fine to be a bit pessimistic too — screw them all.

Safe to say, The Smiths seem to be a sort of salvation for those who never seem to get things right in other people’s eyes. Then again, why would I ever want to get things right in those people’s eyes? Because, see, you shut your mouth, how can you say I go about things the wrong way? I am human, and I need to be loved, just like everybody else does — so the song goes.

Born in 2003, Nur Syada is currently pursuing a degree in Arts English at The University of Malaya. Having a tonne of poetry and prose stashed around, she hopes to become a published poet someday.

Leave a comment