One evening in October, I met the musician S. Razali in his hometown, Ipoh. We had initially agreed to meet at Restaurant Vegas, lured by the promise of its caramel pudding. But at the last minute, he changed his mind, and we settled on Hourglass Cafe, a quiet, small spot nestled between Book Xcess and Sekeping Kong Heng. Several months earlier, S. Razali had quietly released Kembang Mas, his debut EP — a six-track collection that felt like the love child of Sinn Sisamouth, the king of Khmer music, and the Turkish experimentalist Gaye Su Akyol. It arrived in April, not even halfway through the year is a period often deemed treacherous for new releases, prone to slipping into obscurity. Instead, Kembang Mas defied expectations, becoming an instant favourite and perhaps the most discussed EP of the year. S. Razali hardly needed to promote it himself — everyone else did it for him.

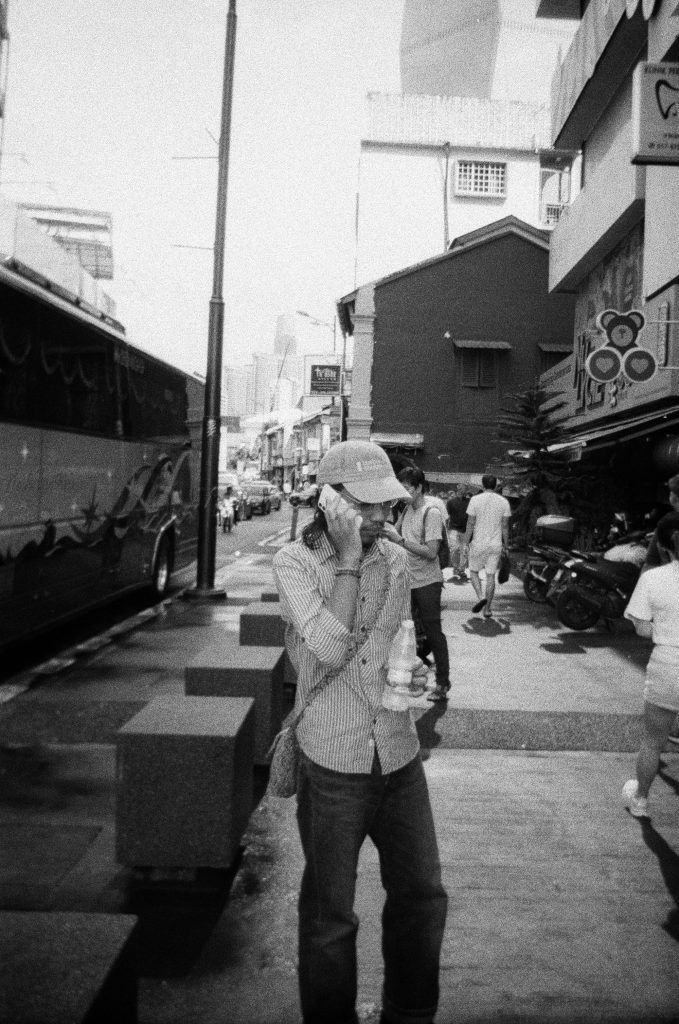

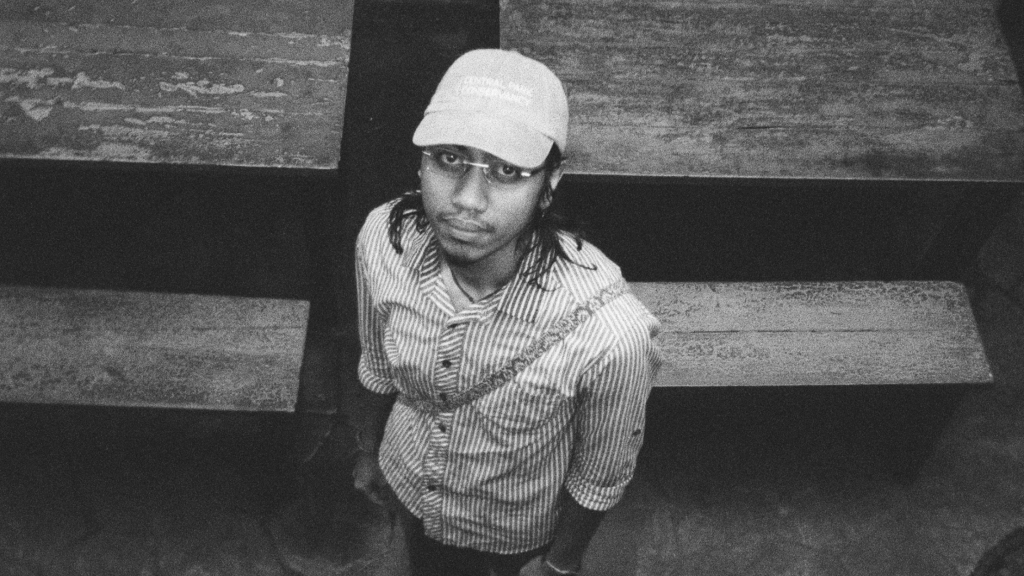

When S. Razali, also known as Saifuddin, arrived at the cafe, he was dressed in a maroon shirt and dark jeans, his wrists adorned with beaded bracelets, silver earrings catching the dim light. He took the seat across from me, and we spoke at length about his music — his love for it, his obsessions, his influences. An hour into our conversation, I finally asked him about the recording process of Kembang Mas, a subject that had long intrigued me given the EP’s intricate world-building and exploration of identity. He hesitated before pulling out the main tool he had used to create it: a case-less, well-worn grey iPhone 11.

Saifuddin opened GarageBand, Apple’s music creation app, and played the finished version of “Krama”, the EP’s fifth track, buried among multiple demos he had been working on. On the screen, I saw the anatomy of “Krama” — a song that takes its name from the traditional Cambodian garment, a national symbol worn around waists, heads and fists as a mark of resistance — layers of instruments stacked atop one another, different colours weaving together into a cohesive whole. “Krama” was the only track on the EP with a small part — the rhythm guitar — recorded on his friend Aiman’s PC, he told me. Everything else was created entirely in GarageBand.

Sometime in 2023, then-20-year-old Saifuddin, began making music on GarageBand. It shouldn’t have been difficult, he thought — he had spent hours at Aiman’s house, the aforementioned friend and also the frontman of the indie rock band Cisco, watching him work on music with Logic Pro. Plus, he could play the piano by ear and picked up the guitar in high school, influenced by friends who immersed him in hardcore music. With those instincts and borrowed know-how, Saifuddin layered instruments over one another, programmed them with mechanical precision and orchestrated his vocals — twangy, uncanny, deliriously shifting from an old man’s rasp to a young woman’s falsetto. He recorded his vocals with nothing but his iPhone speaker.“There’s not much to say about the EP-making process, really,” he said, almost hesitant as if downplaying the simplicity of his setup. No studio. No fancy microphones or instruments. In the labour room of Kembang Mas, there was mostly the raw fidelity of his passion and the GarageBand app.

Saifuddin is twenty-two this year. When he released Kembang Mas in 2024, it rippled through the local music scene almost instantly. I remember that captivating feeling I had when the first notes of “Ulangan” hit. So did a friend. And another. And another. Everyone I expected to love the EP did. Indie rocker and scene observer Mohd Jayzuan recalls nearly falling out of his chair the first time he heard “Tuankanku”, a song that S. Razali wrote and finished just four days before the EP went live. He likened S. Razali’s arrival to that of Takahara Suiko in the 2010s: eccentric, unpredictable, yet unwaveringly true to themselves.

While many may attribute Kembang Mas to be influenced by psychedelic rock slash Anatolian pop, his musical origins trace further back, to his adolescence in a religious school. At 13, his family sent him to a sekolah pondok in Penang, where he was meant to learn discipline and devotion. He remembers crying just three days in. He found the rules to be stifling. Boys and girls were kept apart, with teachers monitoring them at all times. “It was so strict that if you were walking in a corridor, the guys had to press themselves against the wall so the girls could pass,” he chuckled. Then there was the bullying, some older kids punching him over petty misunderstandings. He wanted out.

Yet, it was at sekolah pondok that his love for nasyid music deepened. His family had raised him on nasyid music, with Rabbani CDs constantly in rotation. Born in 2003, he grew up in an era when nasyid had already dominated the mainstream charts, award shows and everyday conversations — not just as religious music but as serious, critical art that shaped Malaysian pop culture. At six, he had his first starstruck moment when he met the late Ustaz Asri, frontman of Rabbani, at the airport. Ustaz Asri greeted him, and for the young boy, it was a pinch-me moment. “You know how people fangirl over One Direction? That was me with Rabbani.”

Much of the EP is shaped by his Cambodian heritage too. Saifuddin’s maternal family hails from Chroy Metrey, a village in Cambodia’s Kandal province. As a child, he visited once a year during school holidays — swimming in the Mekong River, wandering the village with neighbours, and, once, getting bitten by a dog. In “Chroy Metrey” he honours the village’s resilience in preserving its Muslim identity, seamlessly weaving it with Cambodian culture:

Chroy Metrey indahnya rupamu

Mekong menjadi matahari menyala

Agama tanah Arab menjadi pandu

Tanpa menghapus kesenian budaya

Away from the skyscrapers of Phnom Penh, life in Chroy Metrey is modest. Saifuddin’s earliest exposure to Cambodian music wasn’t through Sinn Sisamouth or Ros Sereysothea but through the prayers drifting from funeral ceremonies at the Buddhist temple across the Mekong River. He remembers being eight years old, mesmerised by the rhythmic cadences. “The Cham people aren’t widely exposed to music, except for gendang, so the temple’s prayers were the first sounds that felt like music to me,” he said.

When Saifuddin first emerged in the scene, many were surprised by his age. In preparing for this interview, I asked those who had met him before to describe him, hoping to get a sense of what to expect. Most called him a wise young man, a description I quickly found fitting. Discovering Kembang Mas — a work so rich in depth and world-building — was like stumbling upon a wunderkind moment. One friend described him as “a kid living in an old man’s body.” But his wisdom doesn’t make him any less Gen-Z. In fact, Saifuddin experienced his first brush with recognition not through Kembang Mas, but as Sempudin, his TikTok alter ego. During the pandemic, when TikTok surged as the most dominant social platform, he wasn’t making dalgona coffee or rapid-fire transition videos — instead, he gained traction for parody songs.

Among his viral hits is a nasyid-style reinterpretation of ForceParkBois’ “LOTUS”, which was later used in a video by Luqman Podolski. If GarageBand was his main tool for Kembang Mas, his TikTok success was built on something even simpler: a blue pail used as a drum. There, long before Kembang Mas came to fruition, his absurd creativity and sharp sense of humour had already shined. The parodies earned him calls from ERA FM, 2.6 million likes on TikTok, an Indonesian audience and even a songwriting offer from a record label — one that 18-year-old Saifuddin ultimately declined. Not long after, he wiped some of the videos off the internet, dismissing the period as “cringe” and a form of people-pleasing. He barely wanted to discuss it further.

If his sense of humour was once on full display for strangers to watch and admire, his serious side remains carefully kept behind closed doors. Saifuddin admits that the making of Kembang Mas undeniably brought out the perfectionist in him. Perhaps it was the solitude of working alone that intensified his drive for precision. He set a high standard for the project, aiming to achieve what he called a ‘serabut tapi kemas’ sound — where layers of instruments intertwined without overwhelming each other. He drew inspiration from Anatolian rock, a genre known for its intricate yet seamless blend of guitars, bass, percussion and oud. “They don’t feel too much, they feel just right,” he explained.

His debut single “Ulangan” took the longest to complete — about a month. Saifuddin became fully consumed by the process, refining the track to meet the standard he had envisioned. He passed demos to Aiman, took in his suggestions and kept producing new versions. “Trying to finish the song was the first thing I did when I woke up and the last thing I did before I went to sleep,” he admitted. Every second of the song became an obsession, each detail meticulously shaped to fit his vision.

It wasn’t just about meeting his own standards either. Saifuddin admits that he got lost in the production of “Ulangan” because of how deeply he connected with it. The song reflects the mental exhaustion of a repetitive routine, ending with the voice of an old man nagging — an echo of his parents’ reminders about how their youth was far more productive than his own.

“People often think young folks like me are lazy and stuck in their comfort zones, so I kind of let that frustration out in Ulangan,” he explained.

Both the frustration and the inspiration stemmed from a specific period in his life — when he took a semester off college to work at Fujiyama Records Store. To some, postponing his studies for a retail job seemed unnecessary, something that could be done at any time. But for Saifuddin, it was never about money; it was about being there.

“For me, it was more about meeting Aiman, who was working there, and just being around everyone,” he said. To him, Fujiyama Records wasn’t just a job — it was a space where the passion fueled everything: the records, the coffee, the clothes.

“It was such a cool place. Everyone was so cool.”

After Kembang Mas was released, expectations mounted in ways Saifuddin had never anticipated. Here was someone who had crafted an entire project on his iPhone 11 in his bedroom — so quietly that even his own family only discovered it when they saw strangers promoting his music on Facebook — now suddenly facing an audience that saw something much bigger in him than he saw in himself. People were thanking him for “this” though he wasn’t quite sure what “this” even meant to them. Offers to perform live came flooding in, but the idea of translating Kembang Mas’s layered, intricate sound into a live setting was daunting.

Last July, he gave it a shot, performing his songs for the first time at the opening party of Bijou Cafe in Ara Damansara. It was an acoustic set, with Aiman on guitar alongside him. Just days before, Saifuddin had gotten into a motorcycle accident, so he played with his hand wrapped in a bandage. They played straight through without interludes or interactions, wrapping up the set in just 15 minutes. As people continued urging him to perform Kembang Mas properly, telling him it was a waste not to, the pressure only grew. I asked if he disliked being told what to do. He simply answered, “Yeah” and left it at that.

In an attempt to fulfill people’s request to perform live, Saifuddin put out a call on Instagram months ago for sessionists to join him for live performances. Finding the right people, however, was a longer process than expected — not because he was picky about technical skill, but because he was searching for something deeper. To him, a serious musician isn’t just someone who plays well; it’s someone who can articulate how music shapes their everyday life. “A lot of people treat creativity like just entertainment, but I want someone who sees it as a lifestyle.”

His pursuit of perfection inevitably pushes him toward burnout. “At the start, I’d ask myself, ‘Why do I feel this way?’ But then I realised, oh, it’s part of the process.” He even defended his own tendency to overthink, saying, “When people say overthinking is bad, I actually think it’s a good trait.”

Beyond the weight of his own standards, there was another layer of expectation: the pressure to be the next big name in Nusantara music. The scene has long been hungry for its next defining artist, whether in the vein of Monoloque or the unfulfilled what-ifs of Sang Rawi. With Saifuddin, people latched onto his sound, his intricate compositions and even his half-Cambodian identity, eager to fit him into the Nusantara mould. But he never saw it that way.

“People label Kembang Mas as Nusantara music because of its Cambodian influences, as if that was my goal,” he said. “But I never set out to showcase my identity.”

“The music comes naturally to me. It’s never about proving anything to anyone,” he explained further. “It’s always just about being myself.”

Stream “Kembang Mas” on Bandcamp now:

Farhira Farudin is a Kuala Lumpur-based writer, whose work has appeared in Malaysiakini, MalaysiaNow, Eksentrika and others. She is the founder of Noisy Headspace.

Leave a comment