Tuesdays are the worst day of the week. Even when I was on leave — bedrotting, watching my cats wait for me to stop bedrotting — I still think it’s the worst day of the week. The weekend always feels too far away, and when Monday is a public holiday, the rest of the week carries a strange weight of dread.

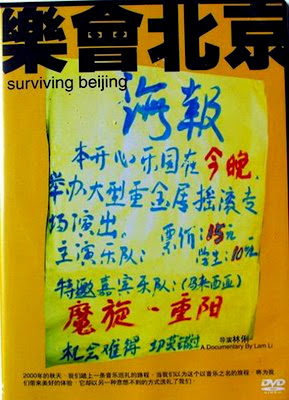

But not last Tuesday. Last Tuesday, I got out of bed, put my phone aside and watched a music documentary called Surviving Beijing. Recommended by a friend, I went into it expecting a travel-style music documentary — something you’d find on Netflix or from any band that brought a videographer along for their international tour. I imagined sit-down interviews and snippets of inside jokes only the band would understand. Documentaries like these often sell the fantasy of a band that has made it, simply because they’ve drawn an audience beyond Malaysia who’s curious enough to watch them. But Surviving Beijing is far from that.

The film follows two Malaysian Chinese bands, Chongyang and Moxuan, on their first-ever tour outside of Malaysia, in Beijing. The tour was organised by Huang Huo, a music collective aiming to breathe fresh air into what they called the “stale Chinese music scene,” then dominated by Hong Kong and Taiwanese pop. The bands gained some traction in Malaysia’s underground scene — when Ipoh was buzzing with BodySurf communities and KL still glorified Pasar Seni punk — with Huang Huo slowly carving out its own space in the spotlight.

Like most bands who’ve toured abroad, you’d expect funny, filthy mishaps born from cultural and language clashes. Stories of sleeping in cramped rooms, sharing meals to afford bus tickets and being mentally drained from long commutes — these are nothing new. Just ask any band that’s had to carry their own gear from one state to another.

But Surviving Beijing presents a more vulnerable portrait.

Recorded on a low-quality handycam by its director Lam Li, with no microphones clipped to the subjects, no stage lights shining on their faces, Surviving Beijing shoves the big questions to musicians who felt too small to perform in a big, foreign country: the material dreams, the kind of passion that seemingly goes nowhere, and what happens when the thing you love starts to drain you.

Much of the tension that explodes on screen seems to have been brewing long before they arrived in Beijing, from within Huang Huo itself. Arguments erupt easily, bickering unfolds, the sunflower seeds are munched on auto pilot mode and the handycam records it all. There’s a rawness to these tense moments, as if staged, except the “actors” are just that good at being ego-driven yet fragile musicians, desperate to be understood in a scene that wasn’t entirely welcoming.

What elevates Surviving Beijing even further is its journalistic backbone. The interviews go beyond the bands and Lin Yue — the Huang Huo newsletter editor, runner, and liaison officer (essentially the glue holding it all together) — to include Beijing’s underground musicians trying to make ends meet, pub owners disappointed by the poor turnout, and even Cui Jian, the elected godfather of Chinese rock. Cui criticises underground musicians for being hypocritical in their rebellion against mainstream culture. The result is an unfiltered portrait of a music scene where passion itself becomes both the maker and the breaker.

I was so fascinated by Surviving Beijing that I didn’t expect this pixelated archive — its bands long disbanded, its collective long dissolved — to become such a haunting mirror of what the underground scene still represents today. And really, has anything changed?

Watch Surviving Beijing on YouTube now:

Leave a comment